After experiencing the horrors of war, Bryan Mealer lost his faith. Morning runs with a priest and a visit to a more welcoming church helped restore it

A few mornings a week, I go running with a priest.

We meet at 5.30 under a streetlamp in central Austin and make our way down to the state capitol building and back, a distance of about eight miles. It’s a routine we started nearly two years ago, and it came during a pivotal point in my life.

I was 40 years old, the father of three small children, and beginning to wrestle with some of the bigger questions that loom at middle age, particularly about faith.

After growing up in the church and leaving for many years – even abandoning my beliefs at one point while covering war – I was contemplating a return. On a visit to my parents, my children had inadvertently exposed a void that I’d been trying to ignore. My three-year-old daughter asked my mother, “What is God?” only to have her brother reply: “Don’t you know, silly? God is Harvey.”

Harvey is what we called our Honda. The look my mother shot me is still burned into my retinas.

I’d also begun writing a book about my family’s saga out in west Texas, how they’d embraced Pentecostalism during the Great Depression and how its promise of salvation had steeled them against poverty and the pain of losing children. Ever since, we’d remained in Assemblies of God and other evangelical churches, where the overriding message was that hell was hot and sin was your ticket. That kind of religious belief still served the needs of many of my relatives, and I didn’t judge them for it.

But it was also the religion of moral crusaders like Dan Patrick, Texas’s lieutenant governor, who wielded “Christian values” like a blunt instrument against gay people and transgender schoolkids, and Roy Moore, who continues to use Christianity as his shield against allegations of child molestation.

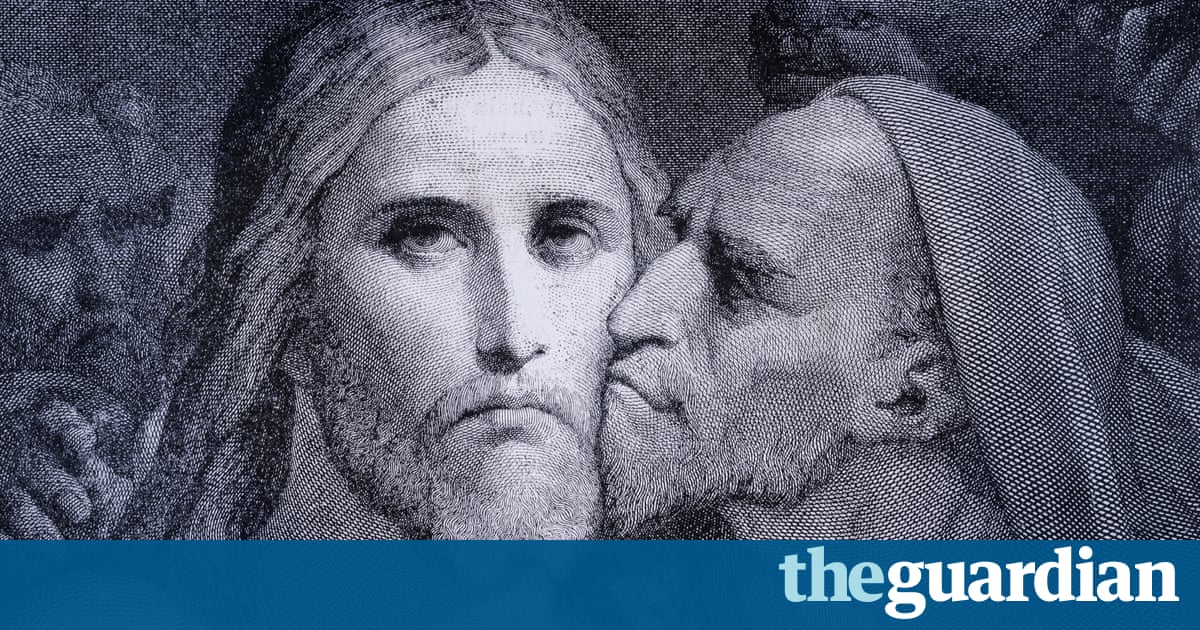

I wondered how could I again call myself Christian, and raise my children to do the same, while feeling separate from that gross distortion of Christ’s message. Decades of culture wars had sullied the whole institution for me and millions of others who stood on the same precipice, looking back in.

I was grappling with these issues when I met David Peters.

David was a priest at an Episcopal church in south Austin and the author of two books. He was also a former marine and chaplain in the army who’d served in Iraq. After the Texas legislature allowed people to openly carry handguns in public and concealed weapons into public universities, David wrote a piece for the Huffington Post advocating the open carry of prayer beads, not bullets. I thought he was a good writer and reached out to chat. Turned out he was also a runner, like me, so we planned to get some miles.

This alone filled another growing void. In the melee of fatherhood and career, I’d started hanging out less and less with my friends. I ran semi-regularly with an old college buddy, Lee, whom I met occasional for a beer, but I had no standing weekly engagements to look forward to. Recent studies show that for men, this middle-age drift into isolation can be more harmful than obesity or smoking. The remedy? No more bowling alone, or running, for that matter.

David and I were in the same situation: we were both 40 with three kids and busy work schedules, and we had little time set aside for friendships. But we both ran, alone, in the early morning, which we’d long claimed as ours. So we started meeting up every Monday, then again on Saturdays with Lee, before eventually adding Thursdays, too. Hot or cold, sleep or no sleep, we ran.

We didn’t start off discussing G-O-D, but our conversation often turned to theology and history. I grew accustomed to hearing David deconstruct the Reformation or Augustine’s libido as we climbed the hills and empty boulevards. But as the months passed by, we began to open up more, and I soon learned that David had experienced his own journey back to faith with some parallels to mine.

He’d grown up in a rigid fundamentalist home, not in Texas but in Maryland and Pennsylvania, where his weekends were spent in airports and knocking on doors, handing out Bible tracts. While his father was a pastor, mine raged and rebelled against the fire and brimstone of his youth. But unable to chart his own spiritual course, he resorted to raising us with what he knew.

Like David, I burned for Jesus while enduring the “can’t dos” of a strict religious upbringing: no Halloweens (it was the devil’s holiday) or secular music. He knew how conflicted I’d felt trashing my Metallica cassettes after a “rock’n’roll seminar” at church.

While David joined the US Marine Corps reserves and enrolled in seminary, I went to college and, like my own father, built a great wall between me and the Lord. While David got married and became a youth pastor at an evangelical church in Pennsylvania, I moved to New York to work in magazines.

But after 9/11, it was war that called us both, and war that would finally rip us from our beliefs.

In 2003, following the invasion of Iraq, David was commissioned as a chaplain in the army and later went to Baghdad. While serving with the 62nd engineer combat battalion, he ministered to traumatized soldiers who’d survived rocket attacks and roadside bombs and lost buddies in the process, and he presided over numerous memorials for the dead. After rotating home, he discovered his wife – and the mother of his two children – had been having an affair.

The marriage ended shortly before his deployment to Walter Reed army medical center, where he worked in the psych and amputee ward with men and women suffering severe trauma. The divorce, plus the crippling depression triggered by his own post-traumatic stress, finally forced a crack in his faith. “I felt like God had abandoned me,” he said. “I was very angry, at myself, my ex, and at the God who I thought would give me an easy life if I did everything right – if I played by his rules. But that God disappeared on me when I needed him most and I was alone. I distanced myself from everything that represented that God – church, faith, hope and love.”

Around the time David joined the army, I moved to Africa to become a freelance correspondent and wound up in eastern Congo, covering a largely neglected war that had killed millions. For three years I reported military operations, massacres, and cholera outbreaks, losing count of how many children I saw buried in some unfamiliar ground where their families had sought refuge.

Eighty per cent of Congolese people identify as Christian, and like my own family during the Depression, they leaned heavily on their faith in times of tragedy. “It’s God’s will,” many would say in response to a militia attack, or an infant who’d succumbed to diarrhea. God was punishing them for not believing, people told me, for theirs was a vengeful god, much like the one I had grown up with, and the god our politicians often hide behind without conscience.

One day while I was visiting a displaced camp, my guide took me on a tour of tents where babies had died during the night, the mothers still cradling the tiny corpses, catatonic with grief. “It’s God’s will,” one woman told me, but I’d grown tired of hearing it.

“Then I want no part of this god,” I thought. As I stood in a haze of cooking fires at the forgotten edge of the world, that god ceased to exist.

On our morning runs, David and I often talk about Paul Tillich, the German American theologian who’d served as a chaplain during the first world war. The carnage of war and its heavy psychological toll pushed Tillich to the brink of his faith and beyond. Tillich hit rock bottom and, while there, came to see God as both everywhere and everything, the very “ground of being”. It was a god who met him in darkness when the other had proved trivial and inadequate.

“The courage to be,” Tillich later wrote, “is rooted in the God who appears when God has disappeared in the anxiety and doubt.”

David had a similar discovery. One dark night, he found himself alone on his balcony, sobbing and cursing God for allowing his life to crumble. “When I stop weeping, I hear a voice,” he wrote in his book, Post-Traumatic God. “The voice is silence … it is a voice that is unconditioned, like a horse standing still.”

Not long after, David left the evangelical faith and became ordained in the Episcopal church, where the ritualistic liturgy offered a kind of spiritual liberation, one that not only helped ease his anxiety and depression, but renewed his bond.

“God has to die,” he said. “The God of our childhood has to shatter in a thousand pieces, die, disappear or change, if we are to have a spiritual life beyond our childhood.” The same eventually happened for my father. During his early 40s, while I was in college, he and my mother left the church for several years before joining a more moderate Lutheran congregation. After decades of seeking, he finally found true spiritual peace.

In the years after leaving Congo, I knew that God was out there somewhere, waiting in whatever form. Around the time I started running with David, my family and I began attending a progressive Methodist church here in Austin, one committed to social justice and offering sanctuary to the LGBT community. Our first Sunday, a man stood up and testified about being ostracized from his previous congregation because he was gay. All he’d wanted to do was worship, and the God who’d met him at Trinity did so with compassion and love, not judgment. I knew I’d found a home, one whose Christian values were suitable for my children.

People might say that my answer was simply finding a church that was liberal, but it’s more than that. I’m reclaiming my faith at a time when American Christianity is in crisis, when the institution of Jesus Christ – a radical humanitarian who was killed by the police – has been co-opted by corporate conservative interests, culture warriors, and the false religion of Fox News, just as it was by slavers and segregationists.

Reclaiming the title is a moral protest against those who attack immigrants, refugees, minorities, and the poor and the sick, the very people whom Christ instructed us to help along the road, and without question. Those stubborn red-letter directives are the same in Roy Moore’s Bible as they are in mine – and yes, I too will fall short in carrying them out.

But at least my path is clear now, the one that I’d been seeking. As scripture tells us, and as Tillich and my father both understood, this journey of faith is best done down a narrow road. There is no room for pulpit politicians or yammering pundits. It’s just God and you – and maybe a priest who met you under the streetlight – putting one foot in front of the other in the dark.

Bryan Mealer’s latest book, The Kings of Big Spring: God, Oil, and One Family’s Search for the American Dream, is out in February.

source http://allofbeer.com/how-i-became-christian-again-my-long-journey-to-find-faith-once-more/

No comments:

Post a Comment